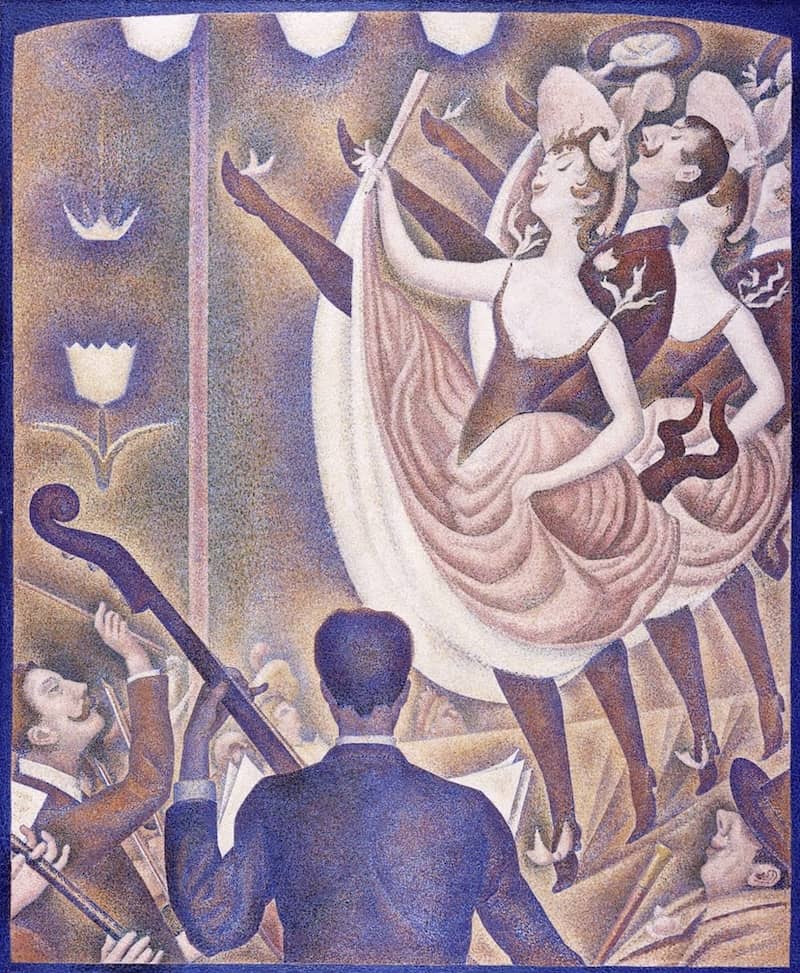

Le Chahut by Georges Seurat

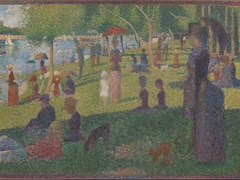

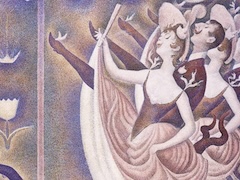

At the Société des Artists lndépendants exhibition in the early spring of 1890, Seurat entered two drawings and nine oils. The paintings included five of Port-en-Bessin and two of the Seine, pictures of austere tranquillity that reworked Impressionist motifs in a new manner. Seurat's largest exhibits were two figure paintings, Young Woman Powdering Herself and Le Chahut. Both are insistently modern and also have more than a touch of caricature and equivocal humor reminiscent of posters and cartoons. Le Chahut, the larger of the two and clearly the more ambitious, was widely discussed by Symbolist critics. A number of these writers were either friends of Seurat or had been granted interviews by him (Alexandre, Christophe, Kahn, Lecomte, van de Velde, Verhaeren, and de Wyzewa). They paid particular attention to two issues: the picture's Montmartre subject and its embodiment of Charles Henry's theories of linear expression. Few praised the picture unstintingly, for its linear structure struck many as too schematic. However, because Henry was an intimate friend of Laforgue, Fen eon, and Kahn and known to the whole Symbolist circle, Seurat's familiarity with his ideas confirmed both men as innovators. In Georges Lecomte's account of Le Chahut, Seurat's contemporaries read that his colors, dominated by the red end of the spectrum, expressed gaiety, as did the many lines and angles that flared upward, including even mouths, eyebrows, and mustaches. The arbitrariness of Seurat's visual signs pleased Lecomte, Feneon, and other Symbolists, who opposed naturalism and praised the hieratic and ritual elements of Le Chahut. Their commentaries unwittingly echoed many of the terms and ideas of Charles Blanc, whose anti-naturalism continued to influence Seurat's art. Blanc discussed Egyptian art in language that the Symbolists might have used for Le Chahut. The figures in Egyptian bas-relief, wrote Blanc:

are accentuated in a concise, summary manner, not without finesse but without details. The lines are straight and long, and the posture is stiff, imposing, and fixed. The legs are usually parallel and held together. The feet touch or point in the same direction and are exactly parallel. ... In this solemn and cabalistic pantomime, the figure conveys signs rather than gestures; it is in a position rather than in action. "

In Le Chahut, we see two women and two men with their legs in the air, a huge bass player, a mustachioed bandleader, two hands on a flute, a smirking male client, and two women peering up from the other side of the stage. The picture does not look like the abstruse theories of Blanc and Henry. Its forms are schematic but not abstract; they are instantly read as images identifying the world of commercialized popular entertainment that had loomed ever larger in Seurat's work after he moved to Montmartre in i886. Le Chahut plunges us into the raucous world of a Montmartre dance renowned for its sexual provocation. The linear accents that incarnate Seurat's theory are also the elements of caricature that dominate the picture's expression. These same linear movements contribute to its posterlike appearance, which is why Seurat's contemporaries linked it with decorative painting. Subject, theory, caricature, and visual appearance are thoroughly intertwined.

In using the term "decorative," reviewers meant the flat appearance of the picture, as distinct from the more varied and rounded forms of earlier painting. Compared with Cafe Concert by Edgar Degas, the kind of work presaging Seurat's, the Le Chahut dancers are lined up with the repetitive rhythms of ornamental art. Parallel to the surface rather than spiraling into depth, they tilt or unfold in staccato bursts that fairly jump in our vision.

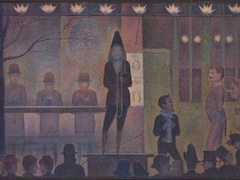

From boyhood Seurat had liked journalistic and popular arts, whose references we detect first in youthful drawings, then in La Grande Jatte, and subsequently in drawings of the cafe-concert. The largest reservoir of circus and cafe-concert images were illustrations and posters, so it was natural that Seurat turned toward them in Circus Sideshow, The Circus, and Le Chahut. By adopting some of their features, he identified his style with his subject matter.